The eternal question! To LMS or not to LMS.

A Learning Management System (LMS) is software (or a software package) or Web-based technology used to plan, implement, and assess a specific learning process. Typically, a learning management system provides an instructor with a way to create and deliver content, monitor student participation, and assess student performance.

With me so far? Good chance that if you're viewing this blog you've had experiences with an LMS of some sorts. Good chance if you have, you've got some mixed feelings about LMSs.

The question of whether to LMS or not has long bugged me. Why? Because when you stack up the reasons for and against there is no clear winner.

|

Reasons FOR

|

Reasons AGAINST

|

|

It helps manage everything in one place

It can often automate workflows (e.g. self-marking quizzes)

You can provide a single training and support model

You often get vendor support for an LMS

You can share objects with others using the LMS

You can have connections with other school software (e.g. timetable

data)

You can have single sign-on options and ease of use opportunities.

|

You are locked into a single system for managing files and workflows

There are often better tools for workflows

It makes people reliant on central training and support models

You have to pay

It stifles people with technical abilities who want to explore beyond

the LMS

The LMS often drives the pedagogy and not the other way round

|

So where do I sit?

Well, let me tell you the story of the last LMS I implemented.

I wanted to do something different with Stage 6 Studies of Religion. I went looking at contemporary models of pedagogy and got stuck on the idea of delivering a blended model that employed flipped learning. So I then sought out an LMS which suited the pedagogical model I was attempting to employ.

That is, my pedagogy drove the LMS decision.

And that is not always the case. Actually, that's almost never the case.

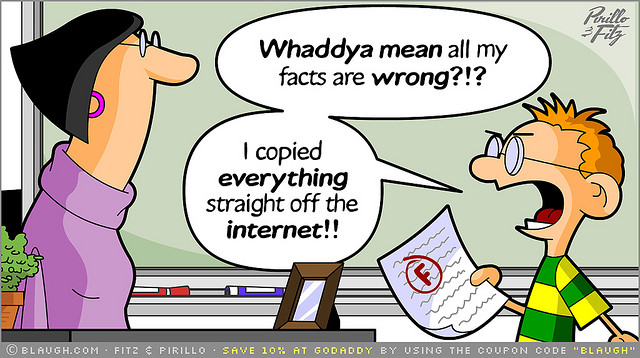

Very rarely do educators say "That's what I want to do!" and backward map to their reality. The start with "That's what I've got!" (often in exasperation) and move forward to their dreams.

I am a firm believer that as educators we are, as Ian Jukes and Simon Breakspear were at pains to point out last week at FutureSchools, 'future makers'. We have an eye on a possible future and an eye on the ground in front and we map out the path to the future.

However, when that eye on the ground in front recognises that not all educators are ready for a post-LMS world, the question of how to get there often brings us back to an LMS reality.

My hunch is that the LMS is the scaffold upon which a digitally rich pedagogy can be built. The question is how comfortable educators are to unlearn an LMS when it is time to leave the nest and fly solo. And of course we could add the further question of how willing systems, like mothers everywhere, are to push them out the nest when the time comes.